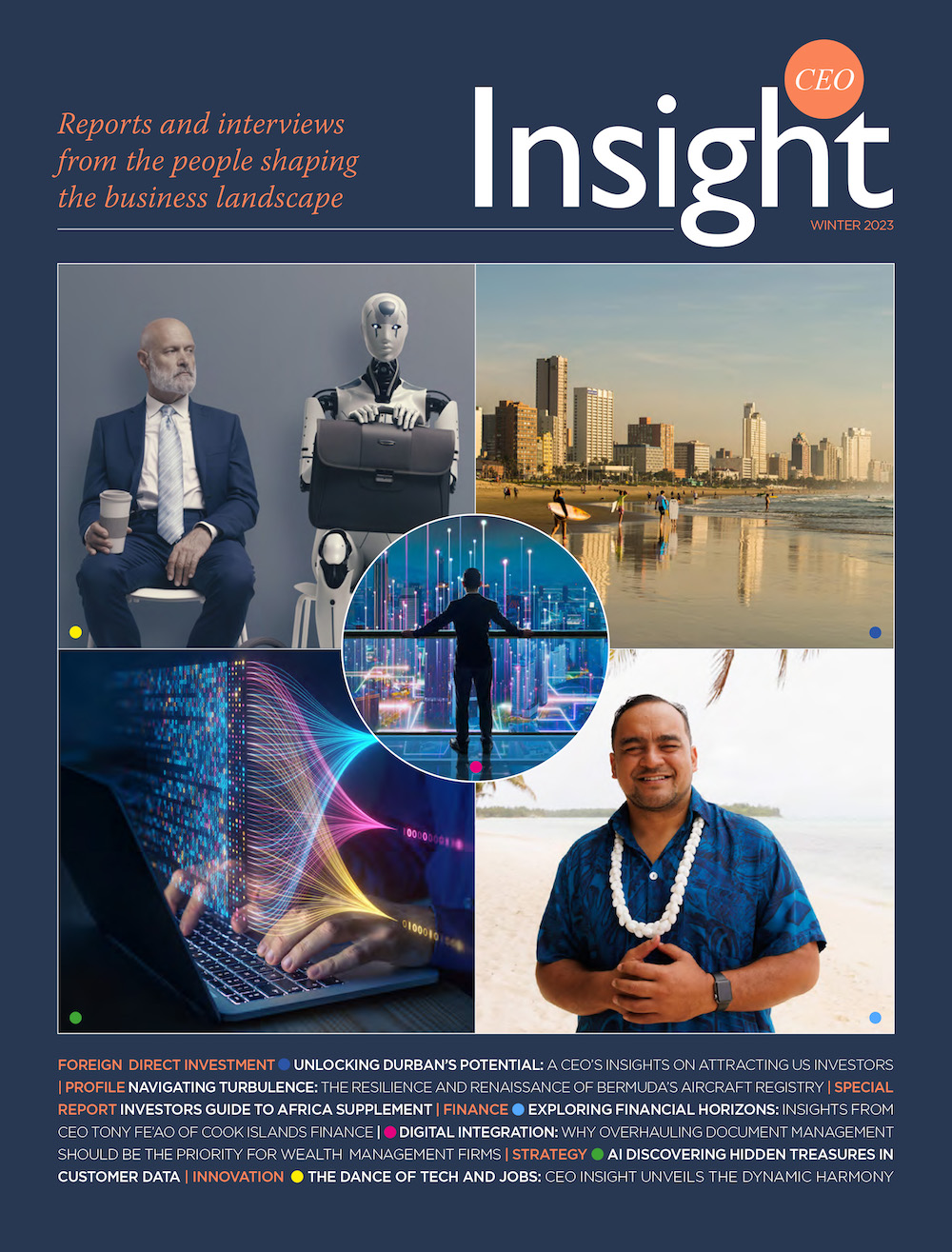

Bad Blood- The Rise and Fall of the Goliath of Medical Tech: Theranos Inc.

Share

In April, beleaguered blood-testing company Theranos Inc laid off most of its workforce. Theranos and its CEO Elizabeth Holmes agreed to settle fraud charges with the US Securities and Exchange Commission, with Holmes surrendering voting control over the company she established, returning millions of shares to the privately held company and paying a $500,000 penalty. Holmes was barred from serving as an officer or director of a public company for 10 years.

Holmes became the world’s youngest female billionaire after starting Theranos aged 19. By promising a technology that would revolutionise the way blood test are done, the young entrepreneur managed to attract millions of dollars from venture capitalists looking to get in on a major invention for medical analysis and health care. Today, almost 13 years later, the scam has been uncovered. The so-called revolutionary technology was nothing but an impossible idea. How did Holmes managed to cover it up for so long? Are there any lessons to be learned from this experience?

Stairway to success

Let’s start at the start. Holmes founded Theranos after dropping out of Stanford’s School of Engineering in 2004. She aimed to make blood testing more accessible by taking only a small amount of blood from the tip of a finger, making it possible to detect and prevent diseases and health risks early on. The idea was revolutionary, as 90% of the tests performed by extracting significantly larger samples of blood would be performed by analysing a single sample from the tip of a finger with her portable device.

After presenting her idea to professors at Stanford University, many doubted the viability of her idea. Among them, Phyllis Gardner, professor of medicine, considered it almost impossible to accurately conduct these tests with such a small amount of blood, as it would only provide limited reliable genetic information. Moreover, finger print samples contain skin cells, debris and other fluids that can affect test results.

Elizabeth Holmes

However, with limited capital, the company rented a lab space. After successfully convincing her Stanford advisor Channing Robertson to take part, Holmes managed to raise $6 million. This eventually turned into almost $700m when investors such as Rupert Murdoch, Carlos Slim, Draper Fisher Jurvetson and Larry Ellison came on board.

These investments were accepted on the condition that the scientific and mechanical aspects behind the functioning of the Edison device – as Holmes named it – and the microLab and microfluid devices weren’t to be revealed to investors or third parties. Holmes would remain in charge of every aspect of the company’s management. As manager, she enforced strict secrecy, following her idol Steve Jobs’ business model, which relied on high levels of protection of technology and information.

In 2009, Ramesh ‘Sunny’ Balwani, who was Holmes’ mentor and partner, became president and COO of Theranos, guaranteeing a $12m injection of capital to keep the company going. With a very well thought out and seductive narrative, Holmes and Balwani made agreements with national pharmacy and drugstore chains like Walgreens, claiming that their device wasn’t commercially ready but that with further investment it should be working within a few years. They managed to collect over $100m in innovation fees to boost the expansion process.

Furthermore, the CEO and COO mislead and even lied to investors about business relationships, current and future deals, growth prospects and expected returns, managing to raise money, grow their capital and position their brand in the medicine sector and in Silicon Valley. They even claimed that the US army in Afghanistan had used their technology and that it was being implemented in medevac helicopters, misrepresenting its deal with the US Department of Defence, as well as claiming to have the endorsement from drug companies and medical companies. These hadn’t given their support publicly.

But the scale of the lies went even further. When US vice president Joe Biden was invited to visit the company’s facility in Newark, Holmes and Balwani set up a fake laboratory to give Biden the impression that Theranos has what in his own words was “the laboratory of the future”.

Meanwhile, Theranos was desperately trying to make Edison and the miniLabs work under the lead of head scientist Ian Gibbons. He would go on to commit suicide after believing he was being fired from the company for not being able to make Holmes’s method work. The company was forced to send out a big portion of its tests to third-party laboratories and was even using blood test analysis devices from other companies rather than its own technology.

By 2014, Theranos and Holmes were widely acclaimed on the tech scene. She made the cover of recognised magazines like Fortune and Forbes. She gave Ted talks and spoke in conferences and panels, sharing the stage with personalities like Bill Clinton and Alibaba’s Jack Ma. With Theranos valued then at $9bn, Holmes was ranked #110 on the Forbes 400 list and was considered the youngest self-made female billionaire in the world. Many were referring to her as “the new Steve Jobs”.

The fall of Theranos’ house of cards

Holmes admiration for Jobs apparently inspired her to replicate his business model. Remaining in control of the technology, making it confidential and subjecting it to strict legal restraints for employees and investors was fundamental to protecting the creation and covering up the reality.

The scam was kept alive via this secrecy and a coercive corporate culture. Moreover, the inability of investors – and of the press and general public – to access technical information about the device or the scientific processes behind it, made it almost impossible to know how the device worked. This started to raise questions from people in and out the medical tech sector.

Holmes and Balwani were constantly qualifying any concerns or doubts as cynical, and employees were often fired or threatened. Although this was an effective method of raising money without having to field too many questions, it was only a matter of time before investors demanded to know whether there was something real behind Holmes’s Silicon Valley speeches about changing the world.

In August 2015, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) visited the company’s lab after complaints about inaccurate results and information provided by Theranos. Simultaneously, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services visited looking for answers after finding major inaccuracies in tests, suggesting that the technology was faulty and that the company was neglecting its quality check-ups, putting the life of patients at risk.

Wall Street Journal reporter John Carreyrou was already investigating the company after finding the extreme secrecy of Theranos very strange, with the CEO always giving vague and shallow explanations about the way her invention worked. After writing almost a dozen articles, Carreyrou unravelled the realities behind the technology, how the company lied and was using third-party traditional blood-testing equipment, and how the young self-made billionaire pulled off a scam of this magnitude.

A few months later, the FDA banned Theranos from using the Edison device, and after retracting or correcting some of the results that the technology had given, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services banned Holmes from owning or managing any kind of laboratory for two years. In March 2018, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) charged the company for leading an elaborate fraud. Holmes committed to pay a $500,000 fine, surrender 19 million shares and was banned from directing a public company for 10 years.

It is possible that Holmes intended at the start to actually develop a device capable of performing accurate tests with small amounts of blood at an accessible price for companies and users. She possibly still believes in her idea and would, if she could, keep researching to try to find a way to make it work. However, promising something she couldn’t deliver and misleading so many people on the basis of a non-existent and probably impossible to develop product, is fraud. Despite their efforts, no matter how high Holmes and Balwani flew, Theranos’ fall and the magnificent scam is all they will be remembered for.

Theranos’ tale is a lesson to investors and the medical tech sector. The disclosure of technical and scientific mechanisms shouldn’t be discretional. When dealing with human lives and health innovation, transparency regarding the functioning of devices and their accuracy should be core to the corporate agenda. Technologies under development should be subjected to established protocols and frameworks to be reviewed, tested and monitored from the early viability analysis stages. Moreover, the completion of development stages should be a prerequisite for further investments to be made. Controls should be created on final products before companies are able to sell the idea as a functioning product.

Theranos has opened the door to a questioning of the limits of secrecy and information control in medical tech. Without doubt, this Silicon Valley Goliath has set out a cautionary tale for future entrepreneurs, investors and clients in terms of reviewing projects and identifying frauds.